It’s not just whitefish: 407 Michigan species on brink amid historic die-off

- Lake whitefish are disappearing from much of the Great Lakes, but they’re not alone

- Invasive species, habitat loss and climate change have wiped out dozens of Michigan species and pushed hundreds more to the brink.

- Experts say society can avoid further losses, but it’s going to take political will that has so far proven hard to come by

Before the lake whitefish there was the blue pike, the Arctic grayling and the lake sturgeon.

One went extinct. Another disappeared from Michigan. The third has avoided extinction because regulators and advocates took action before it was too late.

Those three divergent outcomes lay the stakes for lake whitefish and countless other species amid a global biodiversity crisis that leading scientists have described as “unprecedented.”

“The past has shown us that we, as humans, have a lot of impact on the world we live in,” said Michael Monfils, director of the Michigan Natural Features Inventory, which monitors the state’s species.

“We can also make change, and there’s still a lot of opportunity to have a positive impact on what’s here for future generations.”

Michigan’s iconic whitefish are on the brink of collapse in most of lakes Michigan and Huron, where invasive mussels that arrived via oceangoing ships have filtered away the microorganisms that whitefish rely upon for food.

Sprawling development, pollution, climate change and other invasives threaten yet more Michigan plants and animals, from boreal trees to coldwater trout. State officials have designated 407 species as threatened or endangered, and the list routinely grows.

“Acknowledgement is a necessary first step toward trying to do something about it,” said Steve Lenart, a state fish biologist involved in efforts to protect whitefish.

What we’ve lost

Globally, 1 million species are in danger of extinction, according to a United Nations report that warned species loss is occurring at rates unseen in human history.

Related:

- Iconic whitefish on edge of collapse as Great Lakes biodiversity crisis deepens

- What’s more Michigan than whitefish? Collapse erodes bit of state’s identity

- What are your whitefish memories, Michigan? Beloved fish on the brink

- America’s bats are dying. A Michigan dam may hold a key to their survival

- A rare butterfly makes last stand in Michigan. Feds have $57M plan to save it

- Once near extinction, lake trout are officially recovered in Lake Superior

Michigan’s endangered species list names 76 plants and animals that have disappeared from the state, but it’s an incomplete tally. Some lost species have gone globally extinct, while others persist in other states or countries.

Among them:

Blue pike

A walleye-like fish that once thrived in the deep water of Lake Erie, blue pike were so abundant through the mid-1900s that commercial fishing boats hauled in tens of millions of pounds annually.

Overfishing caused its demise, with help from pollution and invasive sea lamprey that entered the Great Lakes through manmade shipping canals. The last known sighting was in 1962. The US Fish and Wildlife Service declared the blue pike extinct in 1983.

Arctic grayling

Known for their silvery-blue iridescence and large dorsal fin, Arctic grayling were once among the most common fish in northern Michigan rivers.

Logging, overfishing and competition from introduced trout killed off Michigan’s grayling by 1936, although populations still exist in Canada, Alaska and Montana.

Today, the state’s Native American tribes, state natural resources managers and other partners are pursuing a moonshot experiment to return the fish to Up North rivers.

This spring, scientists hatched hundreds of thousands of grayling fry from Alaskan eggs and released them into northern Michigan rivers, hoping they’ll return to spawn by 2029.

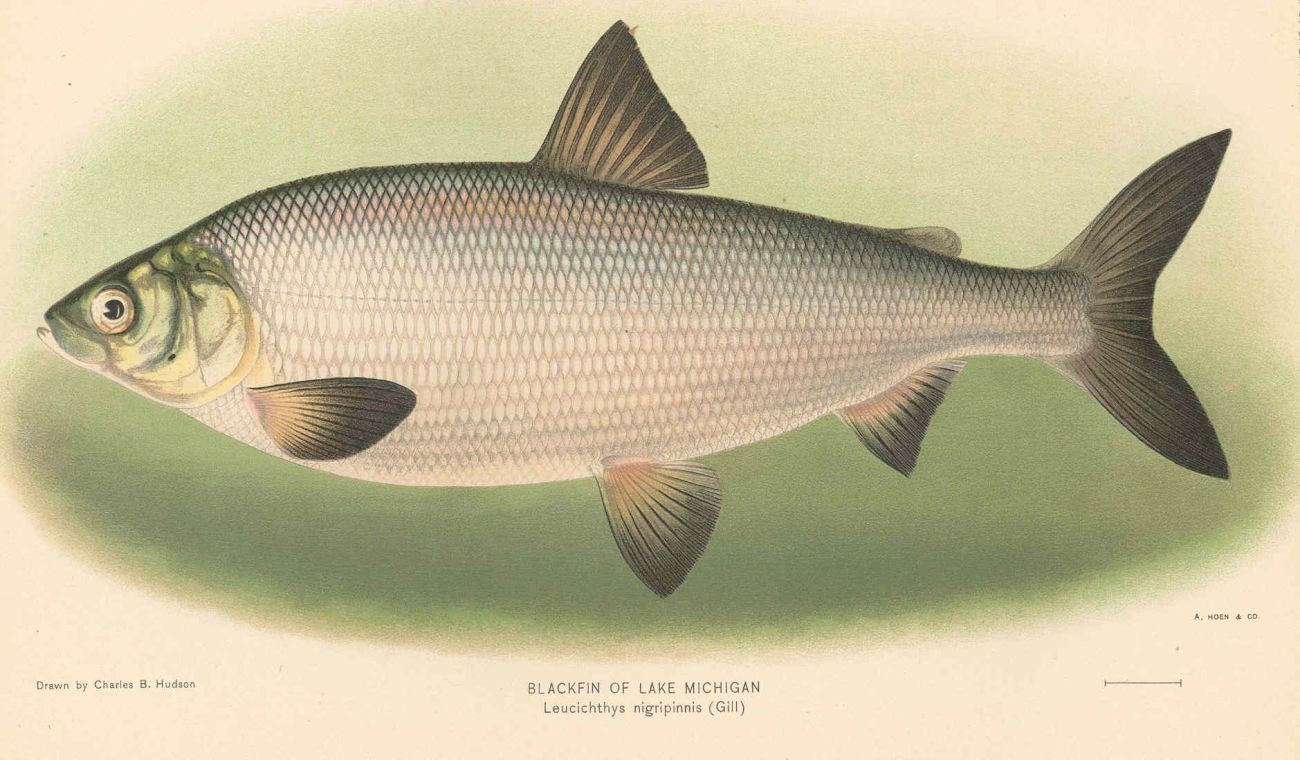

Blackfin, deepwater and longjaw cisco

These three members of the cisco family all once swam in the Great Lakes, but have now either disappeared from Michigan or gone globally extinct.

They fell victim to a familiar mix: overfishing, pollution and predation from invaders wiped them off the map by the mid-1970s.

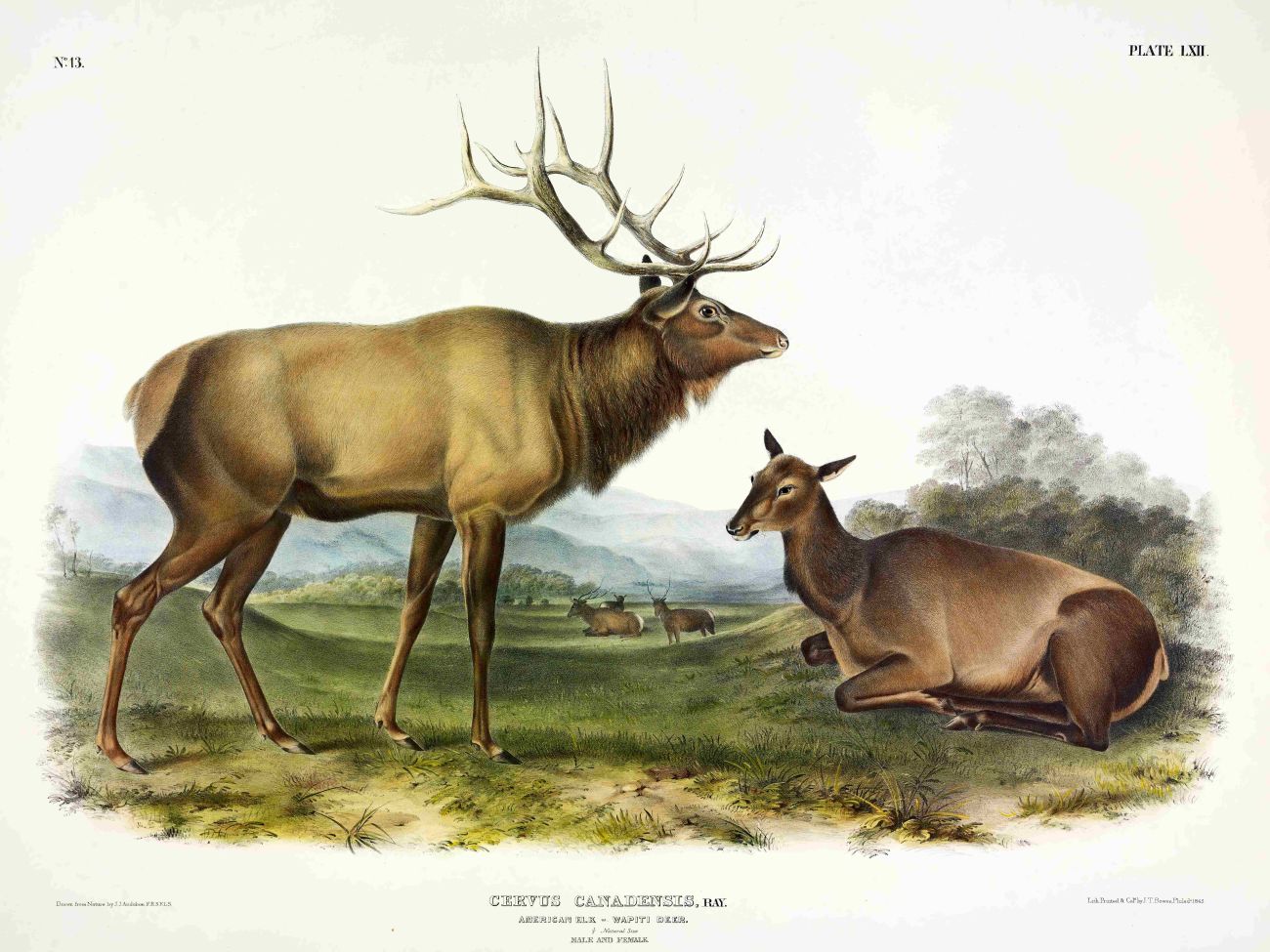

Eastern elk

The famed elk herds that roam Michigan’s Pigeon River Country near Vanderbilt are not native to Michigan. But the state was once home to healthy herds of eastern elk, a larger subspecies that roamed the northern and eastern US and southern Canada by the millions until humans hunted them to extinction in the mid-1800s.

In 1918, government officials relocated several Rocky Mountain elk to Cheboygan County, establishing a population that now numbers roughly 1,000.

Passenger pigeon

Once the most abundant bird in North America, the passenger pigeon was hunted to extinction.

The birds once roosted in Michigan by the millions, feasting on beechnuts in flocks large enough to darken the sky. Their communal instincts made them easy targets for hunters, who killed them en masse. The last known passenger pigeon, a captive bird named Martha, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914.

Barn Owl

Known for their white face, brownish-gray wings, shrieking call and tendency to roost in hollow trees and abandoned buildings, barn owls can be found on every continent but Antarctica, including much of the US.

But not Michigan.

The once-common bird disappeared from the state as humans built over its grassland habitat and killed off its prey with rodenticides. Lone barn owls occasionally turn up in Michigan, but nobody has spotted a breeding pair since 1983.

Lessons from the past

While regulations on logging, hunting, fishing and pollution have eased some pressures that killed off those species, plants and animals today face new threats from invasive species, climate change, habitat loss and new pollutants.

Some, such as the Poweshiek skipperling butterfly, are disappearing faster than scientists can even identify the cause.

“We’re still in the middle of a biodiversity crisis right now, and there’s still so much more that we should be doing,” Monfils said.

The stakes are high.

Humans rely on plants and animals for nearly every aspect of our lives. Bees, butterflies and birds pollinate our food crops — and all are in sharp decline. Bats, which are also disappearing, keep mosquito populations down. And medicinal compounds found in countless plants and animals have served as the basis for life-saving medicines.

Other species benefit society indirectly. Tiny plankton feed small forage fish, which in turn feed the bigger fish that humans like to eat. Without plankton, there would be no whitefish, salmon, walleye or perch.

Even species with no obvious benefit to humans are part of an interconnected web of life that will likely unravel if enough threads are cut, said Elise Zipkin, a Michigan State University professor who studies species decline.

“We really won't know that we’ve hit that point of no return until after it happens,” she said.

There are bright spots: By ceasing some harmful practices of the past, society has managed to pull species like bald eagle, wild turkey and lake sturgeon back from the brink.

The latter nearly disappeared amid rampant overfishing, pollution and habitat loss as humans dammed and denuded the rivers where sturgeon spawn. But strict fishing limits, river restoration and stocking efforts are helping to stabilize the population.

“My hope,” said Mark Zaremski, vice chair of the Native Fish Coalition’s Michigan chapter, “is that we continue to get awareness and consensus that (species preservation) is something that's worth doing.”

Experts say reversing the larger global march toward extinction will take more effort, investment and a willingness to prioritize the planet over convenience and profits.

Many proposals — like limiting sprawl or reducing fossil fuel use — are often politically unpopular.

But there’s a cost to inaction, too, Monfils noted.

“We can't just do what we've been doing for the last 100 years and expect things to change.”

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!